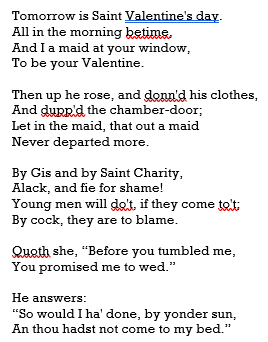

When Valentine’s Day comes around, I think about Ophelia’s madness and a particular song she sings in Act 4, Scene 5 of Hamlet.

At a surface level, the song is Ophelia’s sly, defiant blast at Hamlet’s rejection. Most of what’s been written about Ophelia on a deeper level focuses on the roles of women in society and the strictures of patriarchy that contributed to her madness and death. Recently, Taylor Swift tried to give Ophelia a happy ending in her song “The Fate of Ophelia,” but the tragedy of the cage in which Ophelia was confined—the binary choice between virgin or whore—hasn’t changed as much as we’d like to think in the four hundred years since Shakespeare wrote Hamlet.

Although I was a budding feminist in high school, my initial exposure to Ophelia’s madness in sophomore English class was eye-opening for a different reason.

I went to a large high school in which more than one instructor taught English at each grade level. When we studied Hamlet, my class used a different text of the play than my best friend’s class. In comparing the two books, I noticed that her book omitted the third and fourth verses of Ophelia’s Saint Valentine song, the verses in which Ophelia laments that Hamlet promised to marry her before they had sex, and Hamlet retorts callously that he’d only marry her if she were still a virgin.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, “bowdlerize” means “to remove words or parts from a book, play, or movie that are considered to be unsuitable or offensive.” In high school, I knew nothing of Thomas Bowdler, famous for publishing an expurgated edition of Shakespeare’s plays in the nineteenth century, but I knew censorship when I saw it.

Until that point, I had been a trusting soul (much as virginal Ophelia was when she entered Hamlet’s chamber). I didn’t know authority figures (a textbook, in this case) would lie to me. I was astonished and outraged.

As children, we need reliable guides—parents, teachers, religious figures—while we cope with the many childhood changes in body and brain. Eventually, baby birds must leave the nest and test their wings, and children must leave the black-and-white and soar into the gray.

What did I take away from my teenage revelation?

First, I learned to be circumspect about information: checking one source against others, gauging inherent bias, triangulating truth. This lesson is particularly relevant at this moment in history, when information is easily manipulated and when the sources of information are fractured and partisan.

Second, I ought to call out bad behavior when I see it as Ophelia did: “Young men will do’t, if they come to’t; By cock, they are to blame.” Thus, the essay on Hamlet that I wrote for my sophomore English class was titled “Why Ophelia Was Not a Virgin.”

No responses yet